By Richard Heller

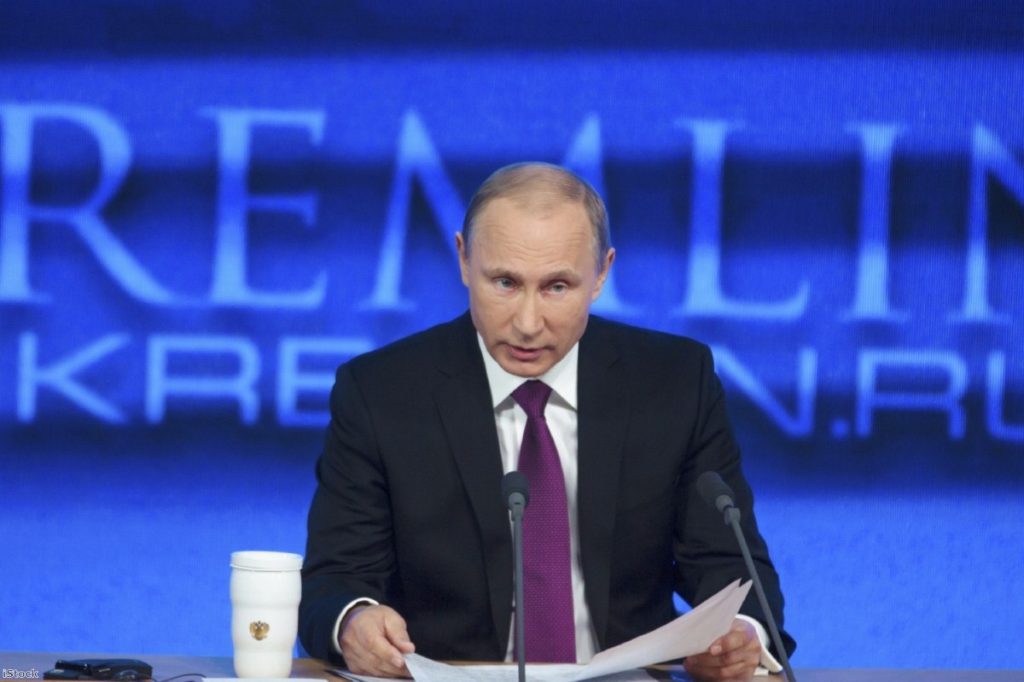

Some days ago I published an article attacking Labour's silence on the behaviour of Vladimir Putin. Predictably, it caused a stream of Twitter rage from Jeremy Corbyn's supporters. But instead of outrage, it's worth taking a little time to really look at the Labour leader's record on the Russian president and see if it stands up to scrutiny.

The reality is, Corbyn has never criticised Putin in the House of Commons nor mentioned him in three speeches to party conference. That sounds like silence to me.

Party conference speeches are especially significant because they are expansive, get lots of press attention, and, above all, allow leaders to set an agenda of their personal choice.

So what did Jeremy choose to say about international policy in those speeches?

In 2015 he (rightly) attacked Saudi Arabia's human rights record. He praised the Obama administration's nuclear deal with Iran. He attacked "the foul and despicable crimes committed by Isil and by the Assad government, including barrel bombs being dropped on civilian targets", but without mentioning Assad's backer, the supplier of those barrel bombs: Vladimir Putin.

In 2016, he attacked Saudi Arabia's war in the Yemen and promised to suspend arms sales to the Saudis and other countries which commit human rights abuses or war crimes. No other international issue was mentioned at all, apart from Brexit, but this was discussed only in domestic terms.

In 2017, he attacked President Trump on climate change. He again attacked the cruel Saudi war in the Yemen, the crushing of democracy in Egypt and Bahrain, and, without blaming anyone in particular, "the tragic loss of life in Congo". He called on Burmese leader Aung San Suu Kyi to end the violence against Muslims in her country. He called for the UN secretary general to create dialogue between the United States and North Korea to "wind down the deeply dangerous confrontation over the Korean peninsula", although even here he carefully avoided any criticism of the North Korean dynastic dictator, who has starved and brutalised his own people while creating a long-range nuclear capability. He supported Palestine. He went back to Trump, calling for Britain to be a "candid friend" and publicly attack his policies on immigration, race, religion and pollution.

But there was no such suggestion of candour towards Putin. The speech set out a foreign policy of preaching and even insults for the leader of our biggest ally, and silence towards the leader of our biggest threat.

None of the three speeches gave any endorsement to Nato or confirmed that Britain, under his premiership, would fulfil its obligations towards each member of that alliance. I could not find any such endorsement online either, just a long history of his calls for Nato to be dissolved and for some kind of neutral or demilitarised zone on Russia's long borders. If that policy means anything, it means conceding to Putin a veto over the right of any adjacent country to invite allies to help defend its frontiers.

Since Corbyn has not talked about Putin and Russia in parliament, or to party conference, or during this year's general election, one has to search online for his views on them. I simply could not find a spontaneous, unprompted criticism of Putin.

Andrew Marr managed to draw two in interviews, but only after extensive questioning. In September last year he induced Corbyn to agree that a Russian attack on a Syrian aid convoy sounded awfully like a war crime. But he covered this immediately with a rambling and irrelevant statement about Syrian refugees.

In November last year, again in response to Marr, Corbyn said he had "many, many criticisms of Putin, of the human rights abuses in Russia and of the militarisation of society" but immediately followed this by repeating his call to "demilitarise" Russia's frontier zones.

In December he wrote to Theresa May condemning "all attacks on civilian targets, including those by Russian and pro-Syrian government forces in Aleppo" – but only after he had been heckled on Syria by Peter Tatchell. (For an excellent defence of this, see Tatchell himself on this site. It is high time Peter Tatchell received a 'People's Peerage'.)

Otherwise, the online cupboard was bare. On Syria, I found many more criticisms from Corbyn of British and American bombing than of the Russian variety – even though Russia has killed many more civilians than the allies

As to Ukraine, I could not find any criticism from Corbyn of any actions by Putin.

There are moments when he flirts with scepticism about Russia. In April this year, he said Putin "can be forced into all sorts of directions if sufficient political and other pressure is put on him”, but then refused to answer questions on the subject at a Federation of Small Businesses meeting.

However, I simply could not find any statement or proposal from Corbyn, since becoming leader, that would create any pressure on Putin to change his current policies. In all, the Labour leader has been largely silent and at best equivocal in his approach to Putin and Russia.

This silence is morally wrong on its own terms as well as politically damaging to him and the Labour party.

Corbyn has developed immense appeal to British voters as a straight-talking man of principle. Such a reputation is very hard to acquire and needs constant maintenance. On international policy, it cannot be compromised by selective attacks on evil, wrongdoing and threats to world peace.

Jeremy Corbyn and his Labour party must decide once and for all whether Putin's Russia represents a threat to ourselves and our allies – or whether his actions are a legitimate response to Western pressures and threats. Does it actually believe, like so-many left-wing stooges for the old Soviet Union, that Russia would become a nicer country if only the West behaved more nicely itself?

Labour should also answer some specific questions.

Does it accept Putin's assertion of a right to protect so-called Russian compatriots in any bordering country? What support will a future Labour government offer to countries which consider themselves under threat from Russia, particularly those formally allied to us through Nato?

What steps, if any, does Labour propose for the restoration of Ukraine's frontiers?

Should the present economic sanctions on Russia be reduced or extended or kept the same?

Does Labour have any new proposals to induce the Russians to release to British justice the alleged murderers of Alexander Litvinenko?

Will Labour do anything to change Russia's dishonest and uncooperative response to the investigation into the shooting-down of the Malaysian airliner over Ukraine more than three years ago, in which ten Britons were killed?

Finally, does Labour believe that Putin's Russia is a fit host for the football World Cup next year? Does it believe that British fans, especially gay ones, will be safe if they choose to go there?

Many people consider Corbyn to be the most likely next inhabitant of No.10. If so, we deserve answers to these questions before he gets there.

Richard Heller was formerly chief of staff to Denis Healey when he was shadow foreign secretary.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.

-01.png)