By Chaminda Jayanetti

There was a hushed awe in the response to this week's Labour conference from Jeremy Corbyn's detractors. Having previously been able to snark and snipe at the succession of mishaps, misadventures and self-inflicted rows that have marked his leadership – interrupted only by last year's general election – this time, for the first time, the tone was one of fearful regard.

'He really wants power', came the words like a revelation, as if the leader of the opposition might be expected to be in it for the money, or the friends, or the ride. Who is it who fights their way to the front of the queue, only to decide not to get on the bus?

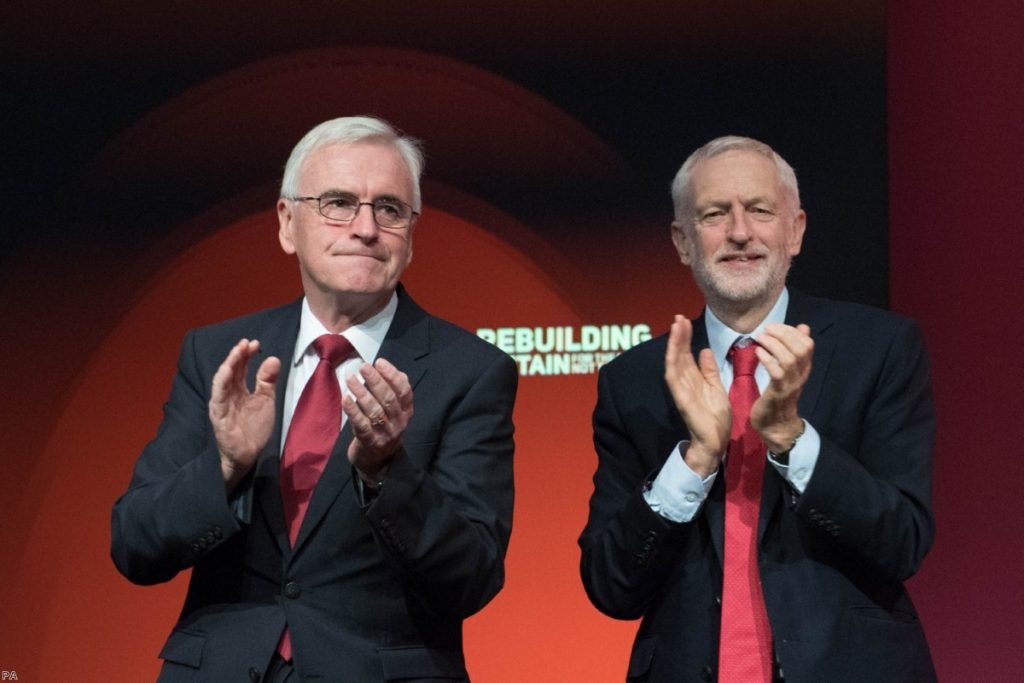

But after a conference in which the leadership manoeuvred its way past its Brexit turmoil, popularised the state-led appropriation of corporate ownership stakes, and rounded off by aiming a party political broadcast like a laser beam at crucial swing voters in English towns, it is clear that Corbyn and McDonnell not only want power – they want a mandate for radical change.

And the old guard, the ancient regime presiding over the status quo, are fearful. In fact, one senses they are quietly petrified as the earth moves beneath their feet. But what are they so worried about? Cynics would say they fear irrelevance. More ideologically, right-wing attacks cast higher public spending as dangerous extremism, usually with the name 'Venezuela' scattered on top like chocolate sprinkles. More credibly, some are concerned by Corbyn's foreign policy stances and his attitude towards anti-Semitism.

However, the biggest single problem with Corbynism is rarely articulated. It is not its policies or even its ugly allies, but what I call the 'Corbyn reflex' – its tendency for knee-jerk reactions against bad news and those who bring it, and for more control to snuff it out.

Corbynism is built on an assumption of having always been right – right about Thatcherism, right about Blair, right about Iraq, right about privatisation, right about Big Finance, right about austerity. Corbynites feel themselves infallible.

Aspects of this are a creation myth. It would be hard to argue that Corbyn was right about the Balkan wars. And he is young enough never to have had responsibility for implementing his worldview – he has spent his Westminster career in opposition to a mainstream that cast aside everything he stands for. Nobody can hold him to account for the decline of British Leyland, for example. He has never failed, for he has never had the chance to.

But armed with the sense of infallibility that comes from this creation story, Corbynites dismiss all criticism of their project. Many critics supported previous leaders whose failings they can be tarred with. Inconvenient facts are dismissed as lies, even in the face of recorded proof. Labour's large and loud online following is regularly wheeled out to drown out dissent.

Anyone who wishes to be heard must first declare fealty to the leadership – Momentum members campaigning for a second Brexit referendum were at pains to point out their unwavering support for Corbyn himself, as if the rights and wrongs of a policy depend on the allegiances of those who back it.

In a sense, this is nothing new. With the exception of the hapless John Major, every prime minister from Margaret Thatcher onwards has wanted to radically refashion Britain in their own image (Gordon Brown moreso as chancellor than leader). Accordingly, they all ensconced themselves in like-thinking bubbles, marginalising dissenters as far as internal party dynamics would allow. And this almost invariably led to both short- and long-term problems.

Thatcher decimated Britain's industrial heartlands and then ran aground with the poll tax. Blair's hubris over Iraq, and Brown's over the economy, wrecked their political project, perhaps forever. David Cameron ignored warnings over the effects of austerity. Theresa May ignored warnings over her immigration policies and Brexit red lines.

No-one is infallible. No-one is omniscient. No-one has a monopoly on the judgement required to make policies work. History tells us this time and time again, and yet no-one seems to learn. Corbynism would just be the latest manifestation of hermetically sealed hubris.

Those of us who are not wedded to free markets may instinctively see Corbynism as more benign than its predecessors. It seeks to reduce inequality, not increase it; increase public spending, not reduce it; define itself by making peace, not war.

But it also seeks the most radical change since Thatcher. It is a paradox that radicalism requires caution if it is not to wreak havoc. Even Thatcher occasionally grasped this, which is why John Moore is a historical footnote rather than the man who destroyed the NHS.

The expansion of state power and control that would come with a Corbyn/McDonnell government would be the most substantial since 1945. A government with the power that Corbyn's desires must not assume omniscience, or marginalise dissenting or supposedly disloyal voices. There are times when your critics know better than you – understanding when to listen to them and when to plough ahead is the toughest nuance of government.

Attlee operated a broad tent. Corbyn's tent is big, but not broad. Shutting out critics when wielding centralised power will lead to policy failure on a massive scale – and when things go wrong, the Corbynite reflex is always towards more control. Already we see a desire for more control of media output, of who runs industries and services, of capital flows, and of whether sitting MPs keep their seats.

We are at a stage where each of these reflexes can individually be defended – the media does behave irresponsibly, corporations and privatised utilities are mismanaged, capital flows do destabilise economies, MPs in safe seats are unchallenged.

But put it all together and a pattern emerges. The leadership's handling of the 'People's Vote' campaign shows its commitment to party democracy dwindles when its own interests are threatened. The Corbynite answer is always to ignore dissent.

Those who expect crisis on day one of a Corbyn government will likely be mistaken – his current policies could lead to growing prosperity for many years, shifting the political consensus in the process. But the reflex will be there, and when things go wrong, or the economy turns south, that is when Corbynism would bare its teeth.

Corbyn and his acolytes have been unexpectedly adept at winning and holding power. They have never shown any recognition of the concept of giving it up.

Chaminda Jayanetti is a freelance journalist. Follow him on Twitter here.

The opinions in politics.co.uk's Comment and Analysis section are those of the author and are no reflection of the views of the website or its owners.

-01.png)